Creative Selection by Ken Kocienda

Publisher: St. Martin's Press (September 4, 2018)

A review with commentary by Jeremy Burnich

Ken Kocienda’s book, “Creative Selection: Inside Apple’s Design Process During the Golden Age of Steve Jobs,” is an entertaining and well-written account of one man’s experience working at Apple. It covers a period roughly from the time of the G4 “Sunflower” iMac (my favorite iMac design) up until the release of the iPad.

There was some very innovative work being done in Cupertino at that time and the author shares snapshots of his contributions including his port of the Safari web browser to his work on the iPhone keyboard.

I didn’t even know who Ken Kocienda was and decided to find out who came up with the original iPhone keyboard after months of frustration typing on my iPhone 10 keyboard.

I googled “iphone keyboard designer” and an article about Ken and his newly published book came up.

Here’s the part that got me:

So you have to make a judgment call, and we did. We had discussions about how should this software behave . . . [and] we decided to err on the side of not inserting obscenities into the text that might be going to your grandma. This issue was something that we dealt with in a related context, which is hate speech. We discovered that we needed to add words that you would never say in polite speech — racial, ethnic slurs. We actually needed to research and get a compendium of these words and add them to the [iPhone] dictionary. Seems like an odd exercise, but those words were in the dictionary, marked specially so that they would never be offered as a correction, so that the software would never assist you in typing these words.

Keyboard complaints aside, I hadn’t considered the thought that went into the iPhone’s touch screen keyboard. I remember picking up the first iPhone the day it came out and the keyboard just worked. It was just how it was and I didn’t give it much consideration.

But reading about that one aspect of one part of a device that a large portion of the world now uses every day clued me into what kind of company Apple was at the time. I was going to read this book.

It is is divided into 10 relatively short and easily digestible chapters. The introduction summarizes what and why he’s going to try to get across and posits that at its core (unintentional pun now intended) Apple is a software company because it’s the software that people use. I can see his point but would argue that thoughtfully considered hardware is essential for good software to be enjoyed. A phone that is uncomfortable to hold or that has an underpowered processor or a weak battery will "spoil the barrel." I think Kocienda would agree (as we’ll see), so I’m not going to argue the point.

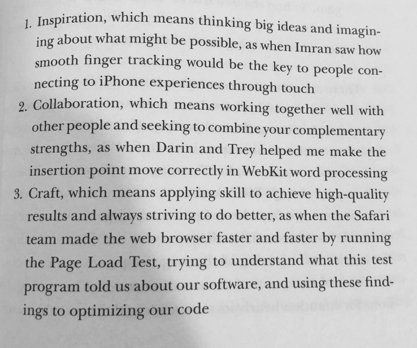

Either way, after contemplating the software made during his tenure at Apple he concludes that the “special sauce” is derived from seven essential ingredients. They are (in no order of importance):

- Inspiration - thinking big and imagining what could be

- Collaboration - working together and seeking to complement each others’ strengths

- Craft - applying the skills you have to achieve the best results you can and striving to continually improve.

- Diligence - doing the work (and showing it) and not hanging on to or harboring excuses for failure.

- Decisiveness - if you are empowered to make a choice, you make it and refuse to delay or procrastinate

- Taste - developing your sense of taste and judgment and finding a balance that produces a pleasing and integrated whole.

- Empathy - trying to see the world from others’ perspectives and creating work that fits into their lives and adapts to their needs

If what you are making consists of these ingredients, according to Kocienda, you are on your way to making something good. It might not be a hit. It might fail. It might not work out but it will have potential.

How are those ingredients mixed?

Probably one of the most important things that Ken talks about in this book is the power, importance, and prominence of “The Demo.” He relates that it set in motion a virtuous circle - one that reinforces and perpetuates the mixing and remixing of the seven ingredients. What you get from this churn is the embodiment of those qualities. It’s very Zen, but he’s very convincing.

The Primacy of The Demo

The Demo is so key to the whole process that it’s the title of the first chapter in the book. Remember how Steve Jobs would do product demonstrations during his keynotes? Well, it turns out that demo was the culmination of hundreds (if not thousands) of smaller demos that took place all over the Apple campus throughout a product’s development.

Kocienda introduces the concept by describing one of those smaller demos . . . that he gave to Steve Jobs. Can you imagine? When I think of presenting something directly to Steve Jobs, I imagine something sort of like this.

That’s a caricature of what it was like but I’m sure people on the receiving end of an unsuccessful demo had the same look on their face as Prince Thun. It’s a given that you wouldn’t be presenting Steve Jobs with some rough around the edges proof of concept that hadn’t been vetted before but it was probably a nerve-wracking experience even under ideal circumstances.

At the same time, these demonstrations were key to determining potential and discerning worthiness of pursuit. Kocienda notes that with these demos, Steve’s goal was to ensure that something was as intuitive and straightforward as possible. He felt this goal was important enough that he was willing to invest his own time, effort, and influence to observe and critique these demos.

Kocienda doesn’t delve into Steve’s temper. It’s well documented that he had one. What he does do is demonstrate that during this “golden age” his temper was tempered by his lieutenants (and that he was a more seasoned and mature person as well). The people Steve surrounded himself with were as important as the man himself. See ingredient two - Collaboration. Henri Lamiraux then the vice president of software engineering melded his strengths (like calmness) to diffuse situations that without such a filter could lead to bruised egos. He acted as a buffer between his team of programmers and the hard to please company executives so that hurt feelings wouldn’t get in the way of the goal. He translated expletive-laden reports into directives his people could follow in the pursuit of making a great product. One aspect of collaboration, one piece of that virtuous circle.

And let's face it, Steve probably had a lot on his mind, had limited time, and had a lot to accomplish. So when Kocienda describes his introduction to perform his demo it feels like he was granted an audience. “Steve, this is Ken. He worked on the iPhone keyboard. He has some tablet keyboard designs to show you.” His work was good enough and the project important enough that he earned that audience.

The Demo was the primary mechanism through which an idea was transformed into something tangible. It was the path walked on the way to the destination - for Kocienda, a fast web browser or an intuitive keyboard. It was the way to achieve the vision articulated by the leader.

Apple was made up of decisive people because they were constantly making and building on decisions via The Demo. It was a process of progress through distillation - to what Ken calls later in the book “convergence,” when all those decisions start coalescing. But it started with the demos.

Making a Demo

Go to an IKEA and there will be dummy TV’s and fake fruit in bowls along with the furniture. The audience is there for the furniture, not the TV’s or produce. According to Kocienda, making a Demo is a lot like those props in IKEA - you have to determine which features you are going to include and which aren’t relevant. To do this you have to considering who will be in the audience.

A demo has to be convincing enough to explore an idea (or be a step towards making a product in a late-stage demo), even if the actual “how” hasn’t been thoroughly explored yet. Initially, look for ways to make quick progress and watch for things that stall progress or that indicate a lack of potential. This is the time where you can cut corners and skip unnecessary effort (via streamlining and removal of distractions) to focus attention on where it needs to be - towards an end goal. Combining inspiration, decisiveness, and craft make for good demos.

Kocienda notes that Steve Jobs was a preparer. He practiced so that his performance looked effortless. Weeks or a month before one of the “Big Announcements” he would begin rehearsing, going over the material until he had the presentation honed and knew it cold. When he observed Jobs’ practice routines, Ken realized that his demos could benefit from similar rehearsal.

At Apple, people weren’t just making demos for the sake of making a demo. Demos were made in the service of achieving a vision. In anything beyond the mundane you need to communicate a well-articulated vision for what you intend to do. That is the starting point and in a sense, you then work backward from there to figure out how to do it.

Coming up with a compelling vision is difficult but it’s the thing that gives focus. This is not a new. Striving for an ideal is something people do all the time, whether it’s an Arthurian idea of kingliness or the example Kocienda uses from Vince Lombardi:

We are going to relentlessly chase perfection, knowing full well that we will not catch it, because perfection is not attainable. But we are going to relentlessly chase it because, in the process, we will catch excellence.

Vince Lombardi

Doing work to accomplish the vision is harder. Generating ideas, building off the ideas, not getting bogged down or lost, or failing outright. A significant part of attaining excellence is closing the gap between accidental and intentional. To be able to achieve a specific and well-chosen thing - not just settling for something - takes hard work and countless wrong turns and missed steps along the way without giving up on the goal.

Results come from work done without losing sight of the goal.

Demos were the system Apple used to keep everyone honest about their work and progress. Even when demos went well, there was always feedback, suggestions for changes, etc. They were an open forum for exchanging ideas about how something could become better. When demos went poorly, Kocienda says there wasn’t finger-pointing. There was constructive criticism. BUT, there was the expectation that the new demos would include a response to the feedback from the previous demos. The one essential expectation: progress.

Demos were concrete examples meant to aid discussion and lead to progress. As an example, he says that a group could talk about what made a "cute puppy." A discussion of the idea of a cute puppy could go on forever. But if you were shown two photos of cute puppies you could make a choice and articulate a reason. Demos did this for ideas. They were manifestations of an idea to make people react and it was those reactions that were essential for driving progress. Direct feedback on one demo provided the impetus to transform it into the next. They were catalysts for creative decisions.

Making demos is hard. You have to overcome apprehension about committing time and effort to an idea you aren’t sure is right. Then you have to expose that idea to smart people. For example, Kocienda states that designing an excellent user experience was as much about preventing negative experiences as facilitating positive ones. Sometimes you make a design decision early on and you have worked hard on it. But you need to be open to seeing that maybe that decision is one of the things holding back progress.

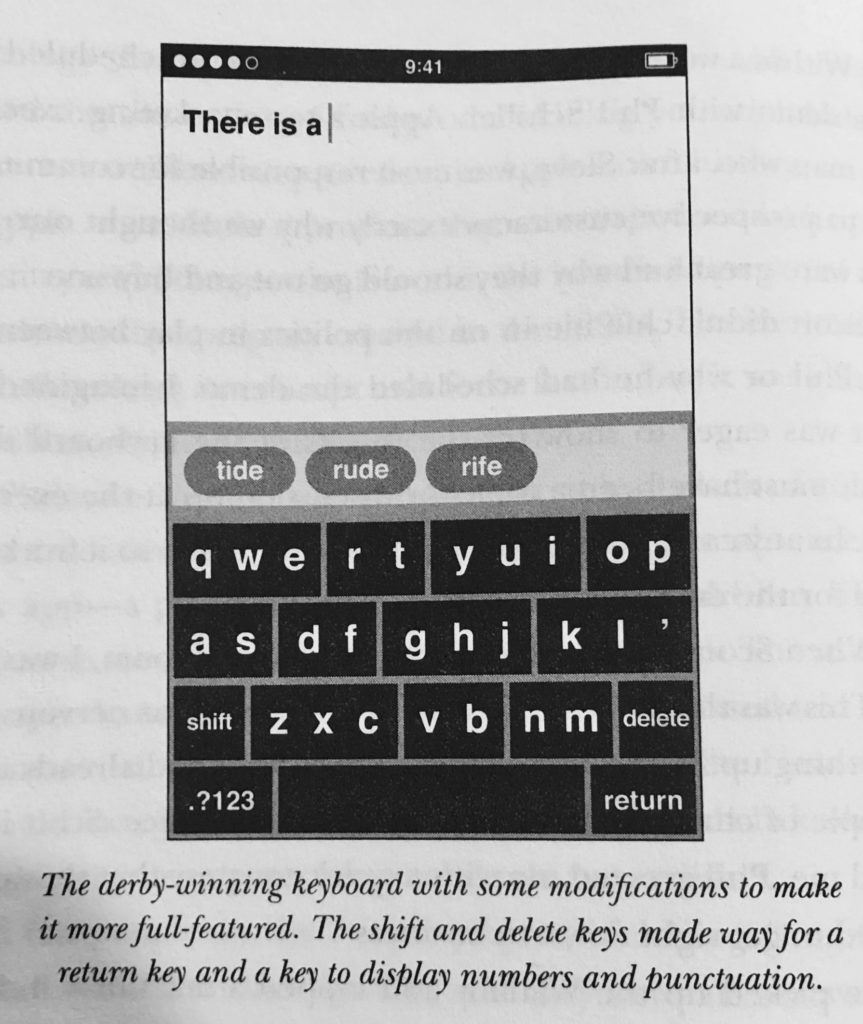

Ken notes that as part of his initial iPhone keyboard he wanted large keys with multiple letters per key. The design had a qwerty arrangement, used tap gestures, and a dictionary to assist. He stuck with the big keys on his design for a long time - it was the best keyboard that any of the Apple designers had come up with. But after several demos and after listening to feedback he realized that "big key" design decision was the thing that had to go to make progress. It had to get simpler. He listened to the users of his design - people on the iPhone team since it was a secret project - because although they weren’t down with the nitty-gritty of keyboard design, they could clearly articulate what needed to be done to make Ken's keyboard better.

A demo isn’t a finished product. A demo is more like a successful audition rather than a sold-out performance.

There is plenty more that you can glean from this book - but the importance of the demo is paramount. There are some fascinating discussions throughout that I haven’t touched on: Convergence - the final phase of making an Apple product; On taste, developing a refined sense of judgement to find the balance that produces a pleasing and integrated whole; and more.

Instead of writing about every single topic I encourage you to READ THIS BOOK. It doesn't have the gossip, politicking, and behind the scenes shenanigans that many books about Apple contain. In fact, if you knew nothing about the various personalities at Apple when Steve was there, you'd be forgiven if you thought that it was some sort of "Kumbaya" idyllic environment. But this isn't a book on people - It's a book on process.

If you want insight into the process that Apple employed during the second reign of Steve Jobs to make "insanely great" products then this book is for you. It’s completely worth your time to read and be a worthy addiction to your library.

Interesting Asides:

Richard Stallman might be one of the most influential people you’ve never heard of. He is a renowned programmer and technology activist who believed all software should be free. With free software, if you are a programmer with a dream for a new app you can go onto the internet and find existing code that you can then tailor to work on your app. Free software made good solutions to common problems readily available.

•

Donald Knuth - a computer scientist who’s not just a computer scientist, he can be considered one of the computer scientists. The author of The Art of Computer Programming - it's a foundational text in the field. He says that programmers waste enormous amounts of time thinking about the speed of non-critical parts of programs and that they should forget about small efficiencies about 97% of the time : “premature optimization is the root of all evil.” There’s a time and a place for optimization.

•

Insight: when software behavior starts getting mysterious, get more organized.

•

If you hit a wall and ask for help and you get it, show direct action. It proves that the people didn’t waste their time helping you and with direct and unequivocal actions those people will like what they see and become invested in your success.

•

Steve on Success: “I think if you do something and it turns out pretty good, then you should go and do something else wonderful. Not dwell on it for too long. Just figure out what’s next.”

•

Steve on Design: Design is how it works. It’s not how it looks. It’s more than just how it looks and feels. It’s how it is. How it works.

Product design should strive for a depth, beauty rooted in what a product does, not merely in how it looks and feels. Objects should explain themselves.

•

The Recipe

Be tasteful and collaborative and diligent and mindful of craft and the rest in all the things we did all the time. Everything counts. Nothing is too small.

A combination of people and commitment. Creative selection and the seven essential elements were the most important product development ingredients, but it took committed people to breathe life into these concepts and transform them into a culture.

No comments.